The First Circuit recently reversed an order compelling arbitration in a putative class action, and in doing so found that Uber could not enforce its terms of service against the Plaintiffs because the hyperlinks to their agreements had been inconspicuous. See Cullilane v. Uber Techs., Inc., 893 F.3d 53 (1st Cir. 2018). When juxtaposed against the Second Circuit’s decision in Meyer v. Uber Technologies, Inc. and the Ninth Circuit’s decision in Wiseley v. Amazon.com, Inc., the decision reinforces that online contract-formation processes should be designed and deployed with the utmost attention to detail.

The Case

The Plaintiffs in Cullinane downloaded the Uber application on their smartphones and then used it to create accounts and order transportation services. They then filed a putative class action that alleged that Uber’s practice of charging toll fees and surcharges violated Massachusetts law. Uber moved to compel arbitration pursuant to the arbitration agreement in its terms of service. The district court granted that motion. But the First Circuit reversed, reasoning that there had not been conspicuous notice of, and thus had not been unambiguous consent to, the terms of service.

The Process

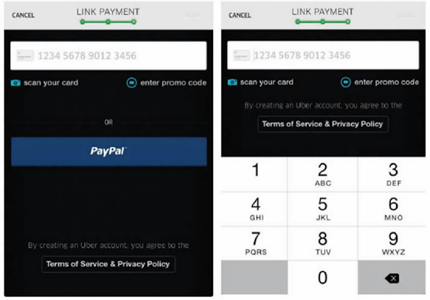

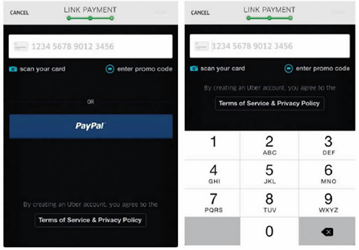

When the Plaintiffs used the Uber app to create their accounts, they encountered three different screens prompting them to enter various user information. The first two screens, which included a “Link Card” screen, required them to enter personally identifiable information. The third screen varied somewhat for each Plaintiff, but essentially prompted them to enter payment information:

Each version of that screen stated that “By creating an Uber account, you agree to the . . . Terms of Service & Privacy Policy.” Although “Terms of Service & Privacy Policy” appeared in bold white text inside a rectangular button, “By creating an Uber account, you agree” appeared in dark gray text. Clicking on the “Terms of Service & Privacy Policy” button would take users to another screen with clickable buttons that would take them to the Terms of Service and the Privacy Policy.

The Decision

The court began by noting that Uber did not claim that any of the Plaintiffs had actually clicked on the “Terms of Service” button. Rather, Uber argued that the notice regarding the terms of service was conspicuous enough to put the Plaintiffs on notice and therefore bind them to the terms of service even if they had chosen not to review it. The court disagreed.

The court observed that a contract-formation dispute might have been avoided altogether if Uber had used “a common method of conspicuously informing users of the existence and location of terms and conditions: requiring users to click a box stating that they agree to a set of terms, often provided by a hyperlink before continuing to the next screen.” Instead, Uber relied on a notice of deemed acceptance, the effectiveness of which turns in large part on the conspicuousness of the notice. Here, the court held, a number of factors combined to make the notice insufficient:

- The link did not have the “common” appearance of “blue and underlined” text, but rather appeared in bold white text inside a rectangular button.

- The “Link Card” and “Link Payment” screens contained other terms displayed with similar features, which diminished the link’s capability to “grab the user’s attention.”

- One version of the “Link Payment” screen included a large blue PayPal button that displaced the hyperlink to the bottom of the screen.

- The “By creating an Uber account, you agree” language appeared in dark gray text in a black field that was no larger or bolder than nearby text.

It should be noted that the court seems to have both understated the importance of the white box that surrounded the “Terms of Service & Privacy Policy” button (as such boxes are a preferred way to emphasize especially important language) and overstated the importance of the dark gray text that was used for the “you agree” language (as such language is largely redundant). Indeed, one could argue that a prominent link to terms and conditions should in and of itself be enough to put a reasonable online shopper on notice that proceeding with the transaction will bind her to those terms. See, e.g., Restatement (Second) of Contracts § 23 cmt. b (1981) (“[A]n offeror or offeree who should be aware of [the terms of a writing] may be bound in accordance with them if he manifests assent.”); id. § 69 cmt. b (“The resulting duty is not merely a duty to pay fair value, but a duty to pay or perform according to the terms of the offer.”). Although the court acknowledged that the link to the agreement had some conspicuous qualities, it found that “the presence of other terms on the same screen with a similar or larger size, typeface, and with more noticeable attributes diminished the hyperlink’s capability to grab the user’s attention.”

The Takeaway

The First Circuit’s ruling reinforces that businesses should carefully consider how hyperlinks to terms of service are displayed on mobile applications. Things as seemingly mundane as the size, type and color of fonts—as well as the presence and presentation of other text on the same webpage—can be critical in satisfying some courts that notice was conspicuous.

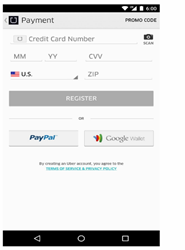

Indeed, the Second Circuit recently found that a slightly different version of the Uber payment screen did provide conspicuous notice of the terms of service:

Cullinane Payment Screens

Meyer Payment Screen

In doing so, it identified a number of factors that supported its conclusion:

- The entire “Payment” screen was visible at once.

- The screen was “uncluttered,” with only the link, “Register” button and payment fields.

- The screen had only two font colors, no other links and no advertisements.

- The linked appeared “directly below” the “Register” button.

- The link was bright, blue, underlined and capitalized.

- The text used to notify users that creation of an Uber account would bind them to the linked terms was displayed in dark contrasting text.

Similarly, the Ninth Circuit found that Amazon’s Terms and Conditions were enforceable, reasoning that the notices regarding the agreement were “in sufficient proximity” to the action buttons for online shoppers to understand that they would be bound to these terms if they proceeded with a purchase.

.svg?rev=a492cc1069df46bdab38f8cb66573f1c&hash=2617C9FE8A7B0BD1C43269B5D5ED9AE2)