Last year, the Southern District of New York refused to enforce Uber’s Terms of Service because it believed that the agreement’s placement was inconspicuous and the consumer’s acceptance was ambiguous. Last week, the Second Circuit vacated that order and found that the agreement had been reasonably disclosed and unambiguously accepted. See Meyer v. Uber Techs, Inc., Nos. 16‐2750, 16‐2752, 2017 WL 3526682 (2d Cir. Aug. 17, 2017). Its application of traditional legal principles to modern commercial problems is a must-read for anyone who designs or defends online contract formation processes.

The Case

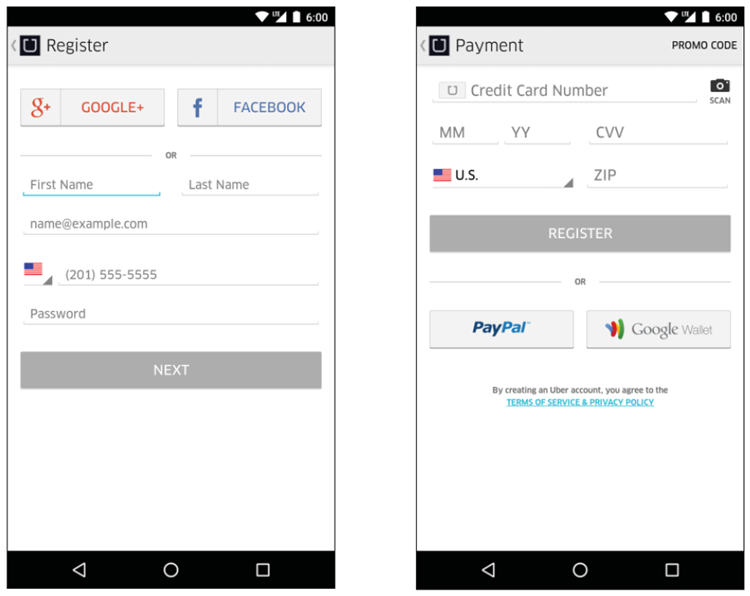

Uber offers a smartphone app that allows riders to request rides from third-party drivers. The Plaintiff in Meyer v. Uber Technologies downloaded the Uber app, created an Uber account, and then used the Uber app multiple times. After he filed a putative class action that alleged that the Uber app allows drivers to illegally fix prices, the Defendants—Uber and its former CEO—moved to compel arbitration pursuant to the arbitration agreement in the Uber Terms of Service. The Defendants supported that Motion with a declaration from a Senior Software Engineer who had determined from Uber’s records when and how the Plaintiff had created his account. The declarant explained that a user who created an account at the same time with the same smartphone would have seen the following two screens:

After downloading the app and clicking a “Register” button, the Plaintiff was first presented with the “Register” screen, which prompted him to choose a registration method (one of which was providing his personally identifying information) and click the “Next” button. After providing his personally identifying information and clicking the “Next” button, the Plaintiff was then presented with the “Payment” screen, which prompted him to choose a payment method (one of which was providing his credit card information) and then click another “Register” button. Below that “Register” button was a notice that stated that, “[b]y creating an Uber account, you agree to the TERMS OF SERVICE & PRIVACY POLICY.” Users who clicked on that hyperlink would have been presented with a third screen with a button that, when clicked, would display the current version of the Terms of Service and its arbitration agreement and class action waiver.

The Plaintiff did not deny any of that. Instead, he claimed that the Terms of Service were not enforceable because he had not noticed the hyperlink—despite its appearing on the same screen in text that was contrasting, capitalized, and underlined—or otherwise known about the Terms of Service. The district court agreed, finding that no agreement had been formed because the Defendants’ notice was inconspicuous and the Plaintiff’s acceptance was ambiguous. The Defendants then took an immediate appeal pursuant to 9 U.S.C. § 16.

The Decision

Actual Notice or Inquiry Notice

The Second Circuit reversed. It began by noting that, although electronic commerce has “exposed courts to many new situations,” it has not “fundamentally changed the principles of contract.” Under those principles, an “electronic ‘click’ can suffice” so long as “the layout and language of the site” provide reasonable notice that “a click will manifest assent to an agreement.” That is true even if the agreement is never read, as a contract will arise if there is either “actual notice” or “inquiry notice” of its terms. Whether an offeree has “inquiry notice” turns on the “clarity and conspicuousness” of the notice, which in this context are “a function of the design and content of the relevant interface.” In short, if an offeree receives “reasonably conspicuous notice” and provides an “unambiguous manifestation of assent,” a contract will be formed even in the absence of actual notice.

The Reasonable Smartphone User

As for what is “reasonable,” the court observed that smartphones are a “pervasive and insistent part of daily life,” and that consumers are accustomed to using them for activities such as shopping and online banking, among others. As a result, the appropriate test in this case was not a “reasonable consumer” test, but a “reasonable smartphone user” test. Under that test, courts should not “presume that the user has never before encountered an app or entered into a contract using a smartphone,” and should instead presume that the user “knows that text that is highlighted in blue and underlined is hyperlinked to another webpage where additional information will be found.”

Reasonably Conspicuous Notice

Having decided on the proper legal standard, the court then found that it had been satisfied. It began by finding that the Plaintiff had received “reasonably conspicuous notice” because the Terms of Service were “coupled with the mechanism for manifesting assent.” It identified several factors that—although not individually dispositive—supported its conclusion:

- The entire “Payment” screen was “visible at once”

- The screen was “uncluttered,” with only the link, fields for payment information, and buttons for registering

- The screen had only two font colors, no other links, and no advertisements

- The link appeared “directly below” the “Register” button

- The link was bright, blue, underlined, and capitalized

- The “[b]y creating an Uber account, you agree” notice was in dark contrasting text

Notably, the court found that it was perfectly reasonable to make the agreement available “only by hyperlink.” Hyperlinks, the court explained, are “the twenty-first century equivalent of turning over the cruise ticket” in that they simply invite consumers to “examine terms of sale that are located somewhere else.” As long as the hyperlink and notice are “reasonably conspicuous,” reasonable smartphone users would have inquiry notice of the terms even if they do not “bother reading” them. The court also rejected the notion that the location of the arbitration agreement within the Terms of Service was problematic, as it appeared under a helpful heading (“Dispute Resolution”) and used bold text to emphasize certain provisions. The court was right to do so not only as a matter of fact (because the arbitration agreement was conspicuous) but also as a matter of law (because the trial court’s contrary conclusion created a heightened notice standard for arbitration agreements specifically rather than contracts generally, which Section 2 of the Federal Arbitration Act expressly prohibits).

Unambiguous Manifestation of Assent

The court concluded that, although the Plaintiff’s assent had not been “express,” it was nevertheless “unambiguous” because he had received “objectively reasonable notice” that, by clicking the “Register” button, he was “agreeing to the terms and conditions accessible via the hyperlink, whether he clicked on the hyperlink or not.” That was especially true here, the court found, because “[t]he registration process clearly contemplated some sort of continuing relationship” that “would require some terms and conditions.”

The court also rejected the notion that the Plaintiff’s conduct was ambiguous because clicking the “Register” button not only accepted the agreement but also created the account. In light of the “transactional context” of the registration, and the “Payment” screen’s warning that users would be bound by the linked terms if they created an account, the “registration flow ma[d]e clear to the user that the linked terms pertain to the action the user is about to take.” As a result, the Plaintiff’s click on the “Register” button “unambiguously manifested his assent” to the Terms of Service.

The Takeaway

The Second Circuit’s ruling was grounded not in the public policy favoring arbitration, but in well-settled principles of contract law. As commerce continues its inexorable march online, it will be imperative that courts apply those principles in a commonsense way that promotes predictability regarding the obligations of consumers and businesses alike. The Second Circuit’s decision does just that.

After the Second Circuit issued its Opinion, the Plaintiff asked it to amend the Opinion to state that, when the action is remanded to the trial court, he could present additional evidence regarding whether the link to the Terms of Service was temporarily obscured when he was providing his credit card number. The Second Circuit denied that Motion but noted that it did so without prejudice to the Plaintiff’s ability to raise the issue with the trial court in the first instance—or the Defendants’ ability to argue that the Plaintiff had waived the issue by not raising it sooner.

.svg?rev=a492cc1069df46bdab38f8cb66573f1c&hash=2617C9FE8A7B0BD1C43269B5D5ED9AE2)