In what can only be described as “out of the box” thinking, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) is proposing to pay physicians for virtual check-ins, and for asynchronous interactions with patients in which the physician responds to a photo or video received from a patient. Both are intended to reduce the need for established patients to make unnecessary trips to the doctor’s office.

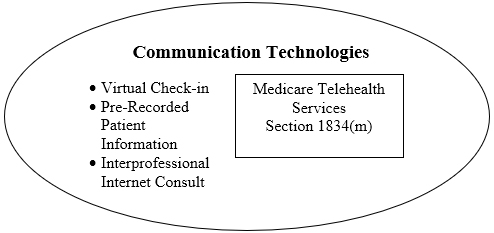

As a part of the proposed Physician Fee Schedule for 2019, CMS recommends exciting changes to reimbursement for digital health services. Historically, CMS has felt constrained with respect to reimbursement for telehealth services by the statutory language found in Section 1834(m) of the Social Security Act. That language limits coverage to certain types of telehealth services — namely real-time, interactive communications, and only those that originate in a certain location (a rural area), from a certain facility (such as a physician office or hospital). CMS now suggests that it is not burdened by the constraints imposed by Section 1834(m) if a particular communication technology falls outside of the definition of a Medicare telehealth service.

Virtual Check-In

One such technology that CMS does not believe fits in the telehealth services box is a “brief communication technology-based service” nicknamed a “Virtual Check-In.” If adopted, this would allow a physician or other practitioner to be reimbursed by Medicare for a brief communication with a patient via some communication technology. Whether that technology is a phone call, a FaceTime interaction, a text or e-mail exchange, at this point is unclear. Recently, Anthem, Samsung and American Well announced that consumers with an Anthem-affiliated health plan will have access to a wide variety of board-certified health care providers for non-emergency medical care 24 hours a day, seven days a week, via an app on their Samsung Galaxy device. Presumably, this could be the kind of communication technology CMS has in mind that it will soon reimburse.

The Virtual Check-In is loosely based on the current CPT Code 99441, which describes a telephone interaction with a patient. Practitioners would bill for this service using a new HCPCS G-code (GVCI1) which would be described as follows:

Brief communication technology-based service, e.g., virtual check-in, by a physician or other qualified health care professional who can report evaluation and management services, provided to an established patient, not originating from a related E/M [Evaluation & Management] service provided within the previous 7 days nor leading to an E/M service or procedure within the next 24 hours or soonest available appointment; 5-10 minutes of medical discussion.

Payment for this service would be around $14, though CMS is seeking comments on the appropriate valuation for this service.

There are some limitations to the proposed reimbursement for this Virtual Check-In.

- Initiated by the Patient. CMS assumes that a Virtual Check-In would be initiated by the patient. The patient could be experiencing a change in condition, and inquiring if medication should be adjusted or if they require in-person attention. Even though the patient initiates the interaction, they may be required to provide some form of consent that recognizes the inherent limitations of the communication technology.

- Available to Established Patients Only. Reimbursement will not be made for these kinds of interactions with new patients and will be available only to established patients, which Medicare defines as one who has been seen by a physician or a member of the physician’s group in the previous three years.

- Separate From E&M Visit. Medicare has historically viewed these occasional interactions between patients and physicians as part of an in-office Evaluation and Management (E&M) service. Here, if the communication is within seven days of a previous E&M visit, or if the communication results in an E&M visit within 24 hours or so, CMS will consider the communication to be bundled with the E&M and will not make separate payment for the service.

Many questions remain regarding the nature of these services and the final payment policy. CMS has asked for comments on a variety of issues, including:

- What types of communication technology are utilized by physicians and other practitioners in furnishing these services, including whether audio-only telephone interactions are sufficient compared to interactions that are enhanced with video or other kinds of data transmission?

- Would it be clinically appropriate to apply a frequency limitation on the use of this code by the same practitioner with the same patient, and what would be a reasonable frequency limitation?

- What timeframes are appropriate for bundling this interaction with an E&M service?

- How can practitioners best document the medical necessity of the service?

CMS clearly believes that if these visits are done well, it will result in an overall reduction in unnecessary visits to the doctor’s office, reducing both the demand on precious practitioner services and the overall cost to the Medicare program.

Remote Evaluation of Pre-Recorded Patient Information

Another service that CMS is proposing to pay for involves the remote evaluation by a practitioner of a picture or video sent in by a patient. As with the Virtual Check-In, CMS believes that such a service is not a “Medicare telehealth service” and is therefore not subject to the constraints imposed by Section 1834(m) of the Social Security Act.

This service is similar in some ways to the Virtual Check-In, and different in other ways. Like the Virtual Check-In, the purpose is to allow patients to communicate with a practitioner to assess a current condition and consider possible changes to medication, or whether the patient should come in to the office. There are similar concerns regarding when this service should be bundled with an E&M service. But in contrast to the Virtual Check-In, which involves a physician-patient communication in real time, this service would cover the physician’s/practitioner’s review of a photo or video taken by a patient and sent in for review.

Practitioners would bill for this service using a new HCPCS G-code (GRAS1), which is described as follows:

Remote evaluation of recorded video and/or images submitted by the patient (e.g., store and forward), including interpretation with verbal follow-up with patient within 24 business hours, not originating from a related E/M service provided within the previous 7 days nor leading to an E/M service or procedure within the next 24 hours or soonest available appointment.

Payment for this service would be around $12, though CMS is seeking comments on the appropriate valuation for this service.

CMS is also seeking comments on whether this service should be limited to established patients. CMS specifically noted that it may be possible for dermatologists and ophthalmologists to review a photo or video and provide a valuable service to a new patient.

Interprofessional Internet Consultation

The third new service that CMS is proposing to reimburse involves consultation by a specialist who may never see the patient. CMS noted the growth of team-based approaches to chronic care management that are made possible by electronic medical record technology. This makes it possible for a treating practitioner to seek advice from a specialist who can review the case and make recommendations on a treatment plan without ever seeing the patient. The communication between the treating practitioner and the specialist could take place over the phone, via an internet portal or via an electronic medical record. Payment would be made both for the treating practitioner (994X0) as well as the specialist (994X6).

In addition to these two proposed codes, CMS is also considering paying for four CPT Codes that were recommended but rejected five years ago:

- 99446 (telephone/ internet assessment and management service provided by a consultative physician including a verbal and written report to the patient’s treating practitioner, 5-10 minutes of medical consultative discussion and review)

- 99447 (same as above, 11-20 minutes)

- 99448 (same as above, 21-30 minutes)

- 99449 (same as above, 31 minutes or more)

CMS believes that payment for these services may reduce cost to the program if the patient does not need to see the specialist for a separate E&M service, but can just consent to a consult by a specialist. CMS expects the patient to be consulted and provide consent to the referral, since the consult may trigger a co-pay.

CMS notes that the need for consults is growing given the rise in patients with chronic conditions and the increased complexity of treating such patients. But a separate visit with the patient is not always necessary when an EMR captures significant detail regarding the patient’s condition, which may be sufficient for a specialist to provide guidance on the case.

CMS is concerned about fraud and abuse issues related to the use of these codes. CMS notes the difficulty of distinguishing between a consult and activities undertaken for the benefit of the practitioner, such as information shared as a professional courtesy or as continuing education. CMS seeks comments on how to best minimize potential program integrity issues. Indeed, the Office of the Inspector General has taken a keen interest in scrutinizing the appropriateness of telehealth service claims, after finding in an April 2018 report that almost one-third of telehealth claims reviewed did not meet program requirements. CMS also seeks comment on whether these services are paid by private payers, and, if so, what controls or limitations have been put in place to ensure that these services are billed appropriately.

Conclusion

It’s significant that CMS believes it is not constrained by Section 1834(m) of the Social Security Act when it comes to new communication technologies. In addition, reimbursement for these innovations could allow Original Medicare to be more similar to Medicare Advantage, where plans must cover Section 1834(m) telehealth services and may also provide additional services like those discussed here. However, providing payment for these services may not immediately trigger a significant volume of such services being provided. CMS estimates that just one million such services would be rendered in the first year, eventually increasing to 19 million annually as more providers offer them. Physician practices will have to operationalize these services. Practitioners will need to be given a certain amount of time between visits to log on to their portal and chat with patients, or review their photos. And specialists will have to determine whether to provide a virtual service for lower reimbursement, or simply require the patient to come to the office for full reimbursement.

Policymakers are only beginning to understand the impact of telehealth on cost reduction, access expansion and quality improvement for the Medicare population. This proposal can help answer these questions and provide payment for services that many providers are already adopting to care for their patients.

.svg?rev=a492cc1069df46bdab38f8cb66573f1c&hash=2617C9FE8A7B0BD1C43269B5D5ED9AE2)